Howton Grove Priory | Mobile WebsiteSharing a Vocation with the World . . .

Feb 2010

A Time for (Temporary) Silence

22/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

The Feast of St Peter's Chair has always been held in great affection by the English. In Anglo-Saxon times, visiting Rome and praying at the tombs of the Apostles was something both kings and clerics delighted in doing. It may seem curiously quaint to some, but praying for our pastors is very necessary; and much more useful than criticizing them!

Talking of prayer, Colophon is not off to Rome, but the monastery bloggers and podcasters feel the need to take more in if they are to give out anything worth reading or hearing. So, no more blogging, podcasting or tweeting until the 1 March; and to make sure she is not tempted back into cyberspace before the feast of St David, Digitalnun is not even going to update the Prayer Box. Instead, you can listen to the daily section of the Rule below; and if you find yourself wondering how to feed your Hendred podcast addiction (oh, the arrogance! Ed), there is still a longish one on Lent on the podcast page, plus 80 others. That should mortify you sufficiently, should it not?

February 23

February 24

February 25

February 26

February 27

February 28

Talking of prayer, Colophon is not off to Rome, but the monastery bloggers and podcasters feel the need to take more in if they are to give out anything worth reading or hearing. So, no more blogging, podcasting or tweeting until the 1 March; and to make sure she is not tempted back into cyberspace before the feast of St David, Digitalnun is not even going to update the Prayer Box. Instead, you can listen to the daily section of the Rule below; and if you find yourself wondering how to feed your Hendred podcast addiction (oh, the arrogance! Ed), there is still a longish one on Lent on the podcast page, plus 80 others. That should mortify you sufficiently, should it not?

February 23

Alternative content

February 24

Alternative content

February 25

Alternative content

February 26

Alternative content

February 27

Alternative content

February 28

Alternative content

A Missionary Faith

19/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

Yesterday we received an interesting suggestion for our next Virtual Chapter: how to reconcile Ash Wednesday's gospel, Matthew 6, with the demands of a missionary Faith. Digitalnun's distractions have been working overtime on the subject so, in an effort to provoke you into joining in the Chapter which we'll hold when we are slightly more back to "normal", here are a few of her half-baked reflections.

On the very day when the gospel told us to let no one know we were fasting, Catholics were walking around with great ashy smudges on their foreheads to proclaim their penitent condition. They may not have been having trumpets sounded when they gave alms, but they were definitely seen by others in church as they attended Mass or other devotions. What are we to make of this? And how do we reconcile the interiority of Christianity with the duty to proclaim the gospel?

First, I think the discrepancy between what the gospel says and what we actually do is worth noting. Ash Wednesday highlights a perennial problem for Christians: we are rather picky about how we interpret the scriptures. By Maundy Thursday we shall be following the gospel literally, washing feet and celebrating a festive meal, but on Ash Wednesday what we do is diametrically opposed to what the gospel says. Or is it?

I myself think that the gospel is pointing to the way in which we can use religion for irreligious ends, to draw attention to ourselves, to portray ourselves as rather better than we are, and certainly better than the next man or woman. Sadly, we can end up believing our own myth: because I go to church on Sundays, tithe my income and fast regularly, I really am a good person. Well, you may be, but you may also be a conceited fool with a heart of stone, blind to your own shortcomings. (A nun's anger, said Newman, is like rapsberry vinegar: sweet acid; I plead guilty).

But what about the duty to proclaim the gospel? It seems very un-English. While Catholics are quite happy to walk around with ashes on their foreheads on Ash Wednesday, they tend to become tongue-tied when asked to explain what they believe. One does not often see them nowadays standing on street corners and proclaiming the Word of God. It may be something of a cop-out to suggest that there is more than one way of proclaiming Jesus Christ. As a contemplative nun, for example, I am sure that the most important thing I can do to spread the gospel is to live monastic life as well as I can, devoting myself to prayer and service in the monastery. I am encouraged in this by the thought that probably the greatest missionary of the nineteenth century was a French Carmelite nun called Thérèse.

But there are times when one must go beyond simply "performing the duties of one's state in life". None of us knows when those times may come, but we can be absolutely sure that we will be given grace when we need it. God never asks what he is unwilling to grant. The problem for us is being ready to listen.

On the very day when the gospel told us to let no one know we were fasting, Catholics were walking around with great ashy smudges on their foreheads to proclaim their penitent condition. They may not have been having trumpets sounded when they gave alms, but they were definitely seen by others in church as they attended Mass or other devotions. What are we to make of this? And how do we reconcile the interiority of Christianity with the duty to proclaim the gospel?

First, I think the discrepancy between what the gospel says and what we actually do is worth noting. Ash Wednesday highlights a perennial problem for Christians: we are rather picky about how we interpret the scriptures. By Maundy Thursday we shall be following the gospel literally, washing feet and celebrating a festive meal, but on Ash Wednesday what we do is diametrically opposed to what the gospel says. Or is it?

I myself think that the gospel is pointing to the way in which we can use religion for irreligious ends, to draw attention to ourselves, to portray ourselves as rather better than we are, and certainly better than the next man or woman. Sadly, we can end up believing our own myth: because I go to church on Sundays, tithe my income and fast regularly, I really am a good person. Well, you may be, but you may also be a conceited fool with a heart of stone, blind to your own shortcomings. (A nun's anger, said Newman, is like rapsberry vinegar: sweet acid; I plead guilty).

But what about the duty to proclaim the gospel? It seems very un-English. While Catholics are quite happy to walk around with ashes on their foreheads on Ash Wednesday, they tend to become tongue-tied when asked to explain what they believe. One does not often see them nowadays standing on street corners and proclaiming the Word of God. It may be something of a cop-out to suggest that there is more than one way of proclaiming Jesus Christ. As a contemplative nun, for example, I am sure that the most important thing I can do to spread the gospel is to live monastic life as well as I can, devoting myself to prayer and service in the monastery. I am encouraged in this by the thought that probably the greatest missionary of the nineteenth century was a French Carmelite nun called Thérèse.

But there are times when one must go beyond simply "performing the duties of one's state in life". None of us knows when those times may come, but we can be absolutely sure that we will be given grace when we need it. God never asks what he is unwilling to grant. The problem for us is being ready to listen.

Ash Wednesday 2010

17/February/2010 Filed in: Chapter Talks

I love Lent. I suspect every monk and nun feels the same sort of exhilaration when Ash Wednesday dawns. There is something immensely attractive about the simplicity of it all. The liturgy becomes very spare: no musical instruments to sustain our voices; no flowers to adorn church or oratory; and only the rich, sombre tones of Lenten purple for vestments and furnishings. Food becomes simpler, too, because we fast every day during Lent (except Sundays, of course). If there is a downside, it is that everybody is so determined to be helpful, to perform little acts of kindness and generosity, that one has to be always on the alert. (Opportunities for almsgiving inside a monastery have to take the form of service because we don't have money to give.)

Part of this year's Lenten chapter talk may be heard on our Podcast page, and there are a few notes on Lent itself on our Liturgy page. One custom we did not mention is that of reading through in its entirety one book of the scriptures as assigned by the superior. This year at Hendred we shall be reading Genesis and Deuteronomy. Without doubt, we shall discover new things in each, just as Lent itself will teach us a great deal.

The life of a monk ought always to have a Lenten quality, says St Benedict. It ought always to be open to the possibilities God offers us. Perhaps that is one lesson we all have to learn anew every year. The simplicity to which we return during Lent is an important part of what we have to learn. As we shed our superfluities, we also shed the carapace with which we try to protect ourselves from God. It is a thought worth pondering as we contemplate what to do for Lent.

Part of this year's Lenten chapter talk may be heard on our Podcast page, and there are a few notes on Lent itself on our Liturgy page. One custom we did not mention is that of reading through in its entirety one book of the scriptures as assigned by the superior. This year at Hendred we shall be reading Genesis and Deuteronomy. Without doubt, we shall discover new things in each, just as Lent itself will teach us a great deal.

The life of a monk ought always to have a Lenten quality, says St Benedict. It ought always to be open to the possibilities God offers us. Perhaps that is one lesson we all have to learn anew every year. The simplicity to which we return during Lent is an important part of what we have to learn. As we shed our superfluities, we also shed the carapace with which we try to protect ourselves from God. It is a thought worth pondering as we contemplate what to do for Lent.

Shrove Tuesday 2010

16/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

Shrove Tuesday is the day on which traditionally we prepare for Lent by receiving the Sacrament of Penance or Reconciliation. For many the idea of confessing one's sins ("being shriven" in old parlance) is hard to understand; for many more it is hard to practise. It may be useful, therefore, to recapitulate what the Sacrament is and why it matters.

Only God can forgive sin. The priest acts in God's name, in accordance with the power and charge given him in the Sacrament of Order; and forgiveness is by no means automatic. The penitent must confess, make satisfaction, perform the penance imposed on him and have a firm purpose of amendment for the future. It is not enough just to rattle off a "laundry list", whip through an Act of Contrition, reel off an "Our Father" or two and assume all is well in this world and the next. Sin matters because it binds us and God wants his children to be free, but we have to do our part in responding to the invitation God makes in this Sacrament.

The first stumbling-block for some is the act of confession. To examine one's conscience in the light of the gospel can be painful in itself. Try reading 1 Corinthinans 13, putting your own name where St Paul puts the word "love" and you will soon see where you are wanting! Trying to articulate this murky side of oneself is certainly humbling, but it is also remarkably liberating. Sin's power over us is the power of darkness and concealment which confession breaks by allowing light and healing in. In a sense, the Sacrament is already work when we realise that we are sinners and have fallen short of God's glory.

Being sorry for one's sins is sometimes another difficulty. Here it is important to remember that it is not what one feels but what one intends that matters. If one is resolved to try one's hardest not to commit a particular sin again, there is no need to try to manufacture a feeling one doesn't honestly feel.

Making satisfaction for one's sins is often overlooked but is absolutely essential. If, for example, one has harmed someone by speaking ill of them, one must do all one can to put matters right. That may require a public humility which makes one squirm. Tough. Sin is serious; so is grace. Or there may be sin that no one but oneself knows about, but that too must be put right if one can. Confessing one's sins to a priest not only reveals them for what they are, it also makes one aware how clever we can be in finding excuses for them or minimizing their importance: having to do something about them strips this false comfort from us.

The penance imposed by the priest refers to the temporal punishment due to sin. By confessing we acknowledge we have injured the whole Body of Christ and we are required to make amends, hence the penance. It must be performed diligently and as soon as possible. Finally, there is that firm purpose of amendment for the future and our gratitude to God for what he has done for us.

Conversion, confession, celebration: this is the threefold pattern of the Sacrament of Penance which prepares us for Lent. It is not all doom and gloom. But before we clear our larders of eggs and fats for the Lenten fast, before we set our first pancake sizzling in the pan, let us remember what Lent is about. It is our great Festival of Freedom as Christians, and a necessary part of our preparation is the acknowledgement of our entanglement in sin.

This week's podcast (to be posted tomorrow) will be longer than usual and will be part of the prioress's Chapter talk for Ash Wednesday.

Only God can forgive sin. The priest acts in God's name, in accordance with the power and charge given him in the Sacrament of Order; and forgiveness is by no means automatic. The penitent must confess, make satisfaction, perform the penance imposed on him and have a firm purpose of amendment for the future. It is not enough just to rattle off a "laundry list", whip through an Act of Contrition, reel off an "Our Father" or two and assume all is well in this world and the next. Sin matters because it binds us and God wants his children to be free, but we have to do our part in responding to the invitation God makes in this Sacrament.

The first stumbling-block for some is the act of confession. To examine one's conscience in the light of the gospel can be painful in itself. Try reading 1 Corinthinans 13, putting your own name where St Paul puts the word "love" and you will soon see where you are wanting! Trying to articulate this murky side of oneself is certainly humbling, but it is also remarkably liberating. Sin's power over us is the power of darkness and concealment which confession breaks by allowing light and healing in. In a sense, the Sacrament is already work when we realise that we are sinners and have fallen short of God's glory.

Being sorry for one's sins is sometimes another difficulty. Here it is important to remember that it is not what one feels but what one intends that matters. If one is resolved to try one's hardest not to commit a particular sin again, there is no need to try to manufacture a feeling one doesn't honestly feel.

Making satisfaction for one's sins is often overlooked but is absolutely essential. If, for example, one has harmed someone by speaking ill of them, one must do all one can to put matters right. That may require a public humility which makes one squirm. Tough. Sin is serious; so is grace. Or there may be sin that no one but oneself knows about, but that too must be put right if one can. Confessing one's sins to a priest not only reveals them for what they are, it also makes one aware how clever we can be in finding excuses for them or minimizing their importance: having to do something about them strips this false comfort from us.

The penance imposed by the priest refers to the temporal punishment due to sin. By confessing we acknowledge we have injured the whole Body of Christ and we are required to make amends, hence the penance. It must be performed diligently and as soon as possible. Finally, there is that firm purpose of amendment for the future and our gratitude to God for what he has done for us.

Conversion, confession, celebration: this is the threefold pattern of the Sacrament of Penance which prepares us for Lent. It is not all doom and gloom. But before we clear our larders of eggs and fats for the Lenten fast, before we set our first pancake sizzling in the pan, let us remember what Lent is about. It is our great Festival of Freedom as Christians, and a necessary part of our preparation is the acknowledgement of our entanglement in sin.

This week's podcast (to be posted tomorrow) will be longer than usual and will be part of the prioress's Chapter talk for Ash Wednesday.

Ars Amandi

14/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

St Valentine's Day does not feature in the monastic calendar. Usually on 14 February we are celebrating the dull but worthy SS Cyril and Methodius (may our Slav brethren forgive me) and meditating on the beauties of Old Church Slavonic rather than the loveliness of the beloved. There is not a red ribbon or rosebud in sight. The feast is too minor to merit a glass of wine or piece of chocolate: everything is suitably drab and dreary. While the commercial world goes into a spin in the name of lurv, we remain relentlessly focused on the spiritual, rejoicing in the preaching of the gospel to our eastern neighbours over a thousand years ago. No wonder many think the Church hopelessly out of touch with the world in which "ordinary people" live and work, unbearably serious and a bit of a kill-joy.

By a happy accident, St Valentine's Day coincides with Sunday this year, so we had the Beatitudes at Mass. I daresay many a preacher compared the two ways of loving, Christian and commercial, contrasting the self-giving of the one with the exploitation of the other. I wonder how many dared to argue that Christian love, as expressed in the Beatitudes, is the most romantic of all loves, because it catches us up into the mystery of Christ's love for his Church, looks to the Other rather than to self and is eternal rather than ephemeral. There are no ribbons and rosebuds to express such love as this, no poetry adequate to proclaim it. Only a morsel of bread and a sip of wine, transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ, can contain the Love "which moves the sun and lesser stars". This is the love-feast of the Christian, the source of all his joy; and we celebrate it, not on just one day of the year, but on every day save Good Friday and Holy Saturday. For us ars amandi, ars vivendi: the art of loving is the art of living.

By a happy accident, St Valentine's Day coincides with Sunday this year, so we had the Beatitudes at Mass. I daresay many a preacher compared the two ways of loving, Christian and commercial, contrasting the self-giving of the one with the exploitation of the other. I wonder how many dared to argue that Christian love, as expressed in the Beatitudes, is the most romantic of all loves, because it catches us up into the mystery of Christ's love for his Church, looks to the Other rather than to self and is eternal rather than ephemeral. There are no ribbons and rosebuds to express such love as this, no poetry adequate to proclaim it. Only a morsel of bread and a sip of wine, transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ, can contain the Love "which moves the sun and lesser stars". This is the love-feast of the Christian, the source of all his joy; and we celebrate it, not on just one day of the year, but on every day save Good Friday and Holy Saturday. For us ars amandi, ars vivendi: the art of loving is the art of living.

The Wasteland Blooms

13/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

Came back from a short trip into Wantage to find our steps covered with a profusion of flowers, orange, white and that delicate shade of green which is almost silver; now the whole house is filled with their scent. It reminds me of the story of the anointing of Jesus' feet. When the jar of nard was broken, says the evangelist, the whole house was filled with the scent. I think monastic life should be like that. There should be a "sweet savour" from the life we lead in Christ which spreads outwards, just as scent spreads outwards from its source. And just as nard was the costliest of scents, stored in alabaster vials, so monastic life should be lavish in its gift of self, however inadequate its human vessels.

To be a vessel of the Spirit is the vocation of every Christian, of course, but monks and nuns are called to empty themselves out even more completely, if possible, that God may be all in all. Only so can the inner wasteland bloom.

To be a vessel of the Spirit is the vocation of every Christian, of course, but monks and nuns are called to empty themselves out even more completely, if possible, that God may be all in all. Only so can the inner wasteland bloom.

Between Sunshine and Snowshowers

11/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

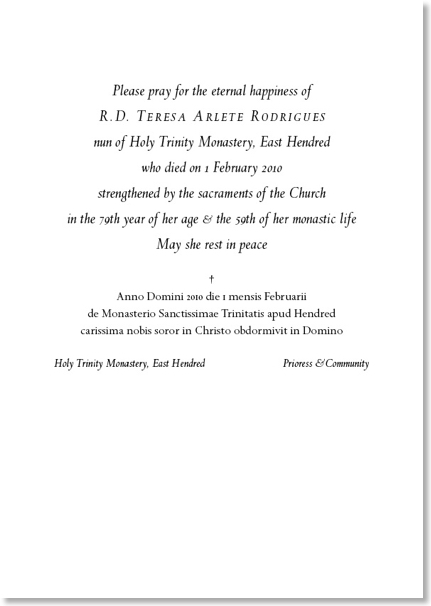

Yesterday we had true "Scholastica weather" and buried D. Teresa amidst sunshine and snowshowers. It was an exhausting day, but we are grateful to all those who came (lots) and all those who helped (lots). I think we managed to combine the monastic and the parochial elements, at least we tried to. It was good to have so many monks and nuns, oblates and friends with us: the church was full, with people having travelled from as far away as Canada in order to be present. A tribute to the huge impact D. Teresa had on those with whom she came into contact, and the high regard in which she was held, not only by us but by many others also. Now we return to the more mundane business of getting on with things, including the dreary "sorting out" that follows any death and the legal matters which can be so time-consuming.

Life has not stopped in the meantime, of course, and we have done our best to keep the business going (needs must pay the bills!) and answer as courteously as we could those who wanted time and attention. Lent is perilously close, but we have decided to scale down our Lent programme for this year as we shall lack one of our principal speakers. There will be a weekly Holy Hour and possibly a couple of talks. Details will be announced later.

Life has not stopped in the meantime, of course, and we have done our best to keep the business going (needs must pay the bills!) and answer as courteously as we could those who wanted time and attention. Lent is perilously close, but we have decided to scale down our Lent programme for this year as we shall lack one of our principal speakers. There will be a weekly Holy Hour and possibly a couple of talks. Details will be announced later.

St Scholastica 2010

10/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

Today is the feast of St Scholastica, sister of St Benedict, a day when strong monks become soppy and strong nuns smile knowingly into their wimples. Scholastica was, above all, a woman of prayer who inspired not only affection but respect in her brother. She knew her own mind and when it came to reconciling the apparently contradictory demands of love and law, seems to have had some insight into the mind of God also. At any rate, she taught St Benedict a lesson he never forgot, for his Rule always sets mercy above judgement, but not in the careless, wishy-washy way of those who are afraid to look Truth in the eye.

This is also the day on which we shall lay D. Teresa's body in the earth, far from her native Trinidad, but in a pleasant English churchyard where the swallows swoop in summer and bats and owls fly about at dusk. The readings at Mass will be Isaiah 25. 6-9; Romans 8.14-23 and John 14. 1-6. I suspect D. Teresa is rather looking forward to the promised Banquet.

This is also the day on which we shall lay D. Teresa's body in the earth, far from her native Trinidad, but in a pleasant English churchyard where the swallows swoop in summer and bats and owls fly about at dusk. The readings at Mass will be Isaiah 25. 6-9; Romans 8.14-23 and John 14. 1-6. I suspect D. Teresa is rather looking forward to the promised Banquet.

Reception of the Body

09/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

Yesterday we clothed D. Teresa in her habit and cowl and laid her in her coffin. Tonight we shall bring her body into church in preparation for the Requiem Mass and Funeral. This "bringing the body to church" has great significance. The church is the place where we are baptized into the life of Christ, where we hear God's word and receive his sacraments; where we worship him in faith and love. It is, in the most literal sense, our "home from home"; for "our true home is in heaven".

So, tonight we shall greet the coffin at the church door and process into church with psalms and prayer. The paschal candle will be lit as a symbol of our hope in the Resurrection. The coffin will be sprinkled with holy water as a reminder of baptism then placed before the altar; the Bible and a Cross will be placed on the coffin as a reminder that we live by the word of God and are made perfect through conformity to Christ's sufferings. FInally, we shall pray, both out loud in words and silently with prayer which needs no outward expression. The Everlasting Arms hold D. Teresa safely in their embrace.

So, tonight we shall greet the coffin at the church door and process into church with psalms and prayer. The paschal candle will be lit as a symbol of our hope in the Resurrection. The coffin will be sprinkled with holy water as a reminder of baptism then placed before the altar; the Bible and a Cross will be placed on the coffin as a reminder that we live by the word of God and are made perfect through conformity to Christ's sufferings. FInally, we shall pray, both out loud in words and silently with prayer which needs no outward expression. The Everlasting Arms hold D. Teresa safely in their embrace.

The Importance of Lectio Divina

08/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

Lectio divina is, first and foremost, the slow, prayerful reading of sacred scripture. Anyone who has read the Rule of St Benedict will recognize its central importance in the life of a monk. One could say that it is the characteristic activity of monastic life since nearly everything we do in choir is, in fact, another form of lectio divina, undertaken by the community as a community rather than as individuals. I, for one, would not confine lectio divina to scripture, anymore than I would claim always to read scripture as lectio divina. Sometimes I read because I have to, or to gain information, and my hurry tends to make me skip some sections and skim others (oh, the advantages of education!), so that I end up with what I want to gain from the text, not necessarily what the author wanted to impart. This is the Fast Food approach to reading, and its consequences can be equally dire.

Lectio divina demands a more leisurely approach, where quality rather than quantity is sought. An important part of the process is the quest for God, allowing the text to speak of God and lead one to prayer. Thus, intention is important; but it is surprising how often one may sit down to something with no conscious intention of doing anything particularly "religious" then find that one has been granted an insight or brought up against a question that forces one to one's knees. My novice mistress looked decidedly sceptical when I confessed that reading Homer turned into prayer and utterly nonplussed when one of my fellows volunteered playing tennis!

What is essential is that lectio divina should be practised regularly, even if for only a few minutes each day. Unfortunately, when very busy, lectio divina tends to get postponed, reduced to a bare minimum or even dropped altogether. During the past week we have had to reduce the time we devote to reading, and we certainly feel the want of it. But perhaps because it wasn't laziness that caused the reduction, I believe there have been compensations. We live in a world where everything and everyone can speak to us of God.

Lectio divina demands a more leisurely approach, where quality rather than quantity is sought. An important part of the process is the quest for God, allowing the text to speak of God and lead one to prayer. Thus, intention is important; but it is surprising how often one may sit down to something with no conscious intention of doing anything particularly "religious" then find that one has been granted an insight or brought up against a question that forces one to one's knees. My novice mistress looked decidedly sceptical when I confessed that reading Homer turned into prayer and utterly nonplussed when one of my fellows volunteered playing tennis!

What is essential is that lectio divina should be practised regularly, even if for only a few minutes each day. Unfortunately, when very busy, lectio divina tends to get postponed, reduced to a bare minimum or even dropped altogether. During the past week we have had to reduce the time we devote to reading, and we certainly feel the want of it. But perhaps because it wasn't laziness that caused the reduction, I believe there have been compensations. We live in a world where everything and everyone can speak to us of God.

In Praise of Water

07/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

Digitalnun has often had occasion to remark that cold water is one of the oldest tastes known to humankind. During the last week she has been reminded how good it is. Whilst prostrate with pain (slight exaggeration: gastro-entiritis is unpleasant and leaves one limp, but it is pretty low in the pain stakes. Ed), she could drink nothing. Then came the craving for water, gallons of the stuff, fresh from the tap, sipped and slurped and really tasted, for the first time in years probably.

Water is one of our commonest sacramentals, beautiful in itself and even more beautiful as a channel of divine grace. It is our "natural element" as Christians. It surrounds us in the womb, it cleanses and refreshes us throughout life. Here in England we usually have enough water to meet all our needs and often all our wants (not quite the same thing). We are never very far from a source of cheap, pure water. Most of us are not very far, either, from a river or sea where we can simply enjoy the gift of water reflecting light back into the air. Perhaps in our weak and wobbly moments, when we feel like water ourselves, we can remember that. Water, just by being water, can make everything luminous; and if you don't believe me, just go into the Fens and look up at the sky.

Water is one of our commonest sacramentals, beautiful in itself and even more beautiful as a channel of divine grace. It is our "natural element" as Christians. It surrounds us in the womb, it cleanses and refreshes us throughout life. Here in England we usually have enough water to meet all our needs and often all our wants (not quite the same thing). We are never very far from a source of cheap, pure water. Most of us are not very far, either, from a river or sea where we can simply enjoy the gift of water reflecting light back into the air. Perhaps in our weak and wobbly moments, when we feel like water ourselves, we can remember that. Water, just by being water, can make everything luminous; and if you don't believe me, just go into the Fens and look up at the sky.

St Paul Miki and Companions

06/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

The feast of St Paul Miki and Companions is a good one for reflecting on loss and gain from a Christian perspective. In case you don't know their story, these are the twenty-six Japanese men and boys (Jesuit priests and brothers, secular Franciscans, cooks and carpenters) who were martyred In Nagasaki by crucifixion in the sixteenth century. As he hung on the cross, Paul Miki, a Jesuit brother and probably the best-known, said, "I am a true Japanese. The only reason for my being killed is that I have taught the doctrine of Christ . . . I hope my blood will fall on my fellow men as a fruitful rain." The persecution of that time looked like the end of everything. It is estimated that a further 40,000 Christians were put to death between their martyrdom in 1597 and the lifting of the ban on Christianity in 1873. The methods of suppression sound familiar: being required to trample on sacred images, not being allowed the scriptures, banning meetings, offering financial inducements to informers and betrayers. Yet when Christian missionaries returned to Japan in the late nineteenth century, they found thousands of Christian living around Nagasaki who had preserved their faith in secret through centuries of fear and oppression.

Why should that surprise anyone? What happened on Calvary must have looked like the end of everything for the first followers of Jesus; but it wasn't. With the benefit of hindsight we can see that the death and resurrection of Jesus are the fons et origo of our life as Christians, quite the opposite of what they must have seemed at the time. The crucifixion of those Nagasaki martyrs must have looked like the end of Christianity in Japan; but it wasn't. It was the beginning of something that even today places the whole Church in their debt.

Just as a community is not really a community unless it numbers the old and sick among its members, those who, in economic terms, are net consumers rather than contributors (the language is as ugly as the attitude), so too a community is not fully a community until some of its members have died and the communion of saints has become a personal reality on both the vertical and the horizontal level. The Nagasaki Christians experienced that when those brave men and boys died on the hill outside their city. It is something our community here in Hendred has begun to experience with the death of our dear D. Teresa. We have suffered the blow; we now confidently await the blessings to follow.

Why should that surprise anyone? What happened on Calvary must have looked like the end of everything for the first followers of Jesus; but it wasn't. With the benefit of hindsight we can see that the death and resurrection of Jesus are the fons et origo of our life as Christians, quite the opposite of what they must have seemed at the time. The crucifixion of those Nagasaki martyrs must have looked like the end of Christianity in Japan; but it wasn't. It was the beginning of something that even today places the whole Church in their debt.

Just as a community is not really a community unless it numbers the old and sick among its members, those who, in economic terms, are net consumers rather than contributors (the language is as ugly as the attitude), so too a community is not fully a community until some of its members have died and the communion of saints has become a personal reality on both the vertical and the horizontal level. The Nagasaki Christians experienced that when those brave men and boys died on the hill outside their city. It is something our community here in Hendred has begun to experience with the death of our dear D. Teresa. We have suffered the blow; we now confidently await the blessings to follow.

Norovirus

04/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

Many thanks for all the kind messages of sympathy and offers of help. Unfortunately, we brought the Norovirus home from hospital with us so it will take a while to respond. We think the funeral will be on Wednesday, the feast of St Scholastica.

Peace and Justice

01/February/2010 Filed in: Jottings

Peace is often elusive at both the personal and the communal level yet it is something we all desire and strive to attain. For a Benedictine, peace is to be found in the daily living out of the Rule in community, in the celebration of the liturgy, prayer, work and study. For each one of us peace will have a different accent, be found in slightly different ways. It may be a line from the psalms that sets our hearts at rest; it may be a theological truth expressed with brilliance and clarity which transforms everything; it may be something as simple and everyday as a shared smile or a PBGV gently indicating that it is time for a walk that stills the inner turbulence. The important thing is not to pretend that the inner turbulence does not exist. Everyone knows moments of doubt and confusion, anxiety and stress. They are part of being human, and it seems to be part of being human that troubles multiply when we feel least able to cope with them. Colophon hasn't any clever suggestions to make, but there is one thought we can perhaps hold onto during the coming week, whatever it brings.

Peace is not the mere absence of war, nor does it exist in a moral vacuum. It is intimately connected with justice; and justice in this context means more a sense of "right order" than what we commonly think of as justice. The right ordering of our lives and of society will never be easy, will always require some effort. Here in the monastery we have a frequent reminder of that. Whenever we go into choir, we make the sign of the cross with holy water. It reminds us of our baptism and serves as a ritual purification before we enter the holy of holies. Sometimes it is more than that: a dose of cold reality to pacify an inner rage or cool a hot temper, even, at times, a welcome draught to water a dry and shrivelled heart. It brings us up short, makes us think what we are doing, challenges us to set right whatever is wrong in our lives. It is an invitation to enter into the peace of the Lord. "Peace and justice have embraced" sings the Psalmist; and where else can they do so but in us?

Peace is not the mere absence of war, nor does it exist in a moral vacuum. It is intimately connected with justice; and justice in this context means more a sense of "right order" than what we commonly think of as justice. The right ordering of our lives and of society will never be easy, will always require some effort. Here in the monastery we have a frequent reminder of that. Whenever we go into choir, we make the sign of the cross with holy water. It reminds us of our baptism and serves as a ritual purification before we enter the holy of holies. Sometimes it is more than that: a dose of cold reality to pacify an inner rage or cool a hot temper, even, at times, a welcome draught to water a dry and shrivelled heart. It brings us up short, makes us think what we are doing, challenges us to set right whatever is wrong in our lives. It is an invitation to enter into the peace of the Lord. "Peace and justice have embraced" sings the Psalmist; and where else can they do so but in us?

Dec 2010

Nov 2010

Oct 2010

Sep 2010

Aug 2010

Jul 2010

Jun 2010

May 2010

Apr 2010

Mar 2010

Feb 2010

Jan 2010

Dec 2009

Nov 2009

Oct 2009

Sep 2009

Aug 2009

Jul 2009

Jun 2009

May 2009

Apr 2009

Mar 2009

Feb 2009

Jan 2009

Dec 2008

Nov 2008

Oct 2008

Sep 2008

Aug 2008

Jul 2008

Jun 2008

May 2008

Apr 2008

Mar 2008

Feb 2008

Jan 2008

Dec 2007

Nov 2007

Oct 2007

Sep 2007

Aug 2007

Jul 2007

Jun 2007

Nov 2010

Oct 2010

Sep 2010

Aug 2010

Jul 2010

Jun 2010

May 2010

Apr 2010

Mar 2010

Feb 2010

Jan 2010

Dec 2009

Nov 2009

Oct 2009

Sep 2009

Aug 2009

Jul 2009

Jun 2009

May 2009

Apr 2009

Mar 2009

Feb 2009

Jan 2009

Dec 2008

Nov 2008

Oct 2008

Sep 2008

Aug 2008

Jul 2008

Jun 2008

May 2008

Apr 2008

Mar 2008

Feb 2008

Jan 2008

Dec 2007

Nov 2007

Oct 2007

Sep 2007

Aug 2007

Jul 2007

Jun 2007